“To triumph fully, evil needs two victories, not one. The first victory happens when an evil deed is perpetrated; the second victory, when evil is returned” -Miroslav Volf

Traumatic experiences and the witnessing of great injustices can have powerful effects. Take, as only one example, our distinct recollections and responses each year to the tragedies of 9/11. A couple days ago, as this anniversary passed, I found myself scrolling through social media’s anecdotes and mourning, for better and for worse. I found myself reflecting again on the enormous social, moral, and ethical influence that event has had in our country. As I saw things like #NeverForget scroll by over and over, I wondered again what a faithful Christian response is toward such moments.

Is never forgetting really a step forward?

What are the results of our deep hurts and resentments?

What might it look like to remember such travesties in a way that seeks reconciliation?

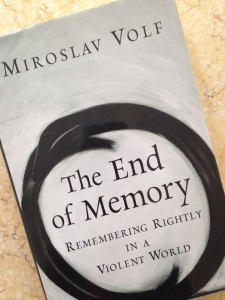

In his book, The End of Memory: Remembering Rightly in a Violent World, Miroslav Volf takes on the arduous and complex task of considering our own process of remembering, from a Christian perspective. Volf, today a theologian and author at Yale, was a young theology graduate married to an American woman and the son of a pastor in former Yugoslavia. In 1984, these characteristics, among others, led to significant suspicions from his fellow servicemen. Volf became the victim of extended, belabored interrogation as a suspected threat to the communist regime.

In his book, The End of Memory: Remembering Rightly in a Violent World, Miroslav Volf takes on the arduous and complex task of considering our own process of remembering, from a Christian perspective. Volf, today a theologian and author at Yale, was a young theology graduate married to an American woman and the son of a pastor in former Yugoslavia. In 1984, these characteristics, among others, led to significant suspicions from his fellow servicemen. Volf became the victim of extended, belabored interrogation as a suspected threat to the communist regime.

Volf writes from the honesty of his own experience, hoping to orient our own reflections of the violence and evil in our world around who we understand God to be. His work reminds us that our memory and reactions to evil, however apparent or subtle they may be, are crucial to the Christian’s own experience and embodiment of God’s work of reconciliation in the world.

Volf writes from the honesty of his own experience, hoping to orient our own reflections of the violence and evil in our world around who we understand God to be. His work reminds us that our memory and reactions to evil, however apparent or subtle they may be, are crucial to the Christian’s own experience and embodiment of God’s work of reconciliation in the world.

The memory of wrongdoing has powerful effect. When given over to an unbridled sense of retribution, the evil of the perpetrator is not, contrary to popular thought, ended. It, instead, further violates the victim through the vicious cycle of continued violence. The maxim “violence breeds violence” comes to mind as Volf points toward the hope and power of true reconciliation. His work is rooted in the scandalous reality of Christ’s life, death, and resurrection:

“The death of Christ understood as an act of grace is an undeniable offense against dues-paying morality governed by a need to restore the balance disturbed by transgressions” (111).

Volf’s topic is clear: “the memory of wrongdoing suffered by a person who desires neither to hate nor to disregard but to love the wrongdoer” (9). To pursue it further he uses three questions: Should we remember? How should we remember? and How long should we remember?

In short, our memories help to form our identity. They are needed. But they are needed because they are a part of healing. They are needed because they produce justice by acknowledging the reality of wrongs, linking us with other victims, and protecting victims from further violence.

But remembering wrongly can also wound, breed indifference, reinforce false identities, and re-injure.

Remembering wrongly is what happens when we allow ourselves to become obsessed with the distinction between victim and violator. Remembering wrongly happens when we allow the memory of wrongdoing to strengthen our anger and resentment. Remembering wrongly occurs when we become men and women who build barriers between victim and violator rather than seeking to tear them down.

Again, this is not to suggest that we should not do any remembering at all. No doubt, “to remember a wrongdoing is to struggle against it.” Acknowledgement cannot be skipped. The evil of violators must be exposed and justice brought forward.

But, we too often subscribe to the narrative that further violence is a path to justice, or that further violence and wrongdoing (directed now at the perpetrator) somehow serve the victim. So, How should we remember?

How should Christians remember?

We must remember truthfully, and we must remember so as to heal, Volf suggests.

The remembering we must learn to embrace is a “remembering that is truthful and just, that heals individuals without injuring others, that allows the past to motivate a just struggle for justice and the grace-filled work of reconciliation” (128).

If, as Christians, we believe that the ultimate goal of creation is a reconciliation of all things, the full and utter reparation of the world, all things being set to rights, then it ought to also follow that we pursue this kind of reconciliation in the present. Though we anticipate full reconciliation as a future reality, our understanding of who God is and what his justice looks like ought to leave our notions of payback and retribution and so-called justice quivering in their inadequacy.

“If One died for the salvation of all, should we not hope for the salvation of all?… Moreover, Christ died to reconcile human beings to one another, not only to God.” (16).

Remembering rightly is the much more difficult task of allowing past offenses to make us agents of peace, healing, and justice rather than arbiters of wrath, revenge, or indifference. And to remember rightly is not simply to forgive a wrongdoer, but to love the wrongdoer.

Our memory of wrongdoing must never become a weapon. Our memories of wrongdoings and violence must not be held in the hands of our own attempts to understand the world, but rather, these memories must be held up in the light of God’s larger story of redemption long enough to see that true redemption and true reconciliation come when wrongdoings are fully acknowledged and then forgotten. The grace-filled world we look forward to and the manner in which that reality has become the story of every truly Christian experience demands that our remembering bring about healing and restoration.

In failing to remember rightly, we perpetuate the violence we abhor. In those moments, “the just sword of memory often severs the very good it seeks to defend” (18).

While these are far from simple pursuits and difficult to speak of in moments of victimization, we soon learn that the cost of remembering wrongly is paid by every party involved.

The Christian story offers a “framework for remembering.” And when we fail to consider our own intentions in light of this framework, we lose sight of God’s redemption in our midst.

The Christian story is a story that offers us, as violators, perpetrators, and offenders, the freedom to find a new and undeserved identity awarded to us in the grace and mercy of Christ.

The Christian story is about becoming, with God, an agent of this reconciliation, an example of enemy-love, and a co-laborer in the hard work of boundary-crossing community.

The Christian story is one that anticipates “the end of memory,” recognizing that “memories of suffered wrongs will not come to the minds of the citizens of the world to come, for in it they will perfectly enjoy God and one another in God” (177).

In this world of perpetual violence, immeasurable hostility, and painful tragedies, let us guard against the temptation to remember wrongly, the temptation to allow our memories to perpetuate and justify the very evil we wish to extinguish.

“To triumph fully, evil needs two victories, not one. The first victory happens when an evil deed is perpetrated; the second victory, when evil is returned” –Miroslav Volf